Honestly, we always meant to remodel the house. We bought property in the neighborhood we wanted to live in, and the house was in rough enough shape that we could mostly afford it. We’ve done the important things like replacing the roof and updating the electric, but could never quite figure out how far we wanted to go with the rest. All we knew was that if we wanted to keep the square footage we have, something needed to be done about the steep, narrow, actively treacherous stairs.

If you’ve talked to me at all about houses in the past ten years, I’ve undoubtedly mentioned my stairs. I hate them. They are difficult for our whole family to manage, but I get stuck on them at least once every day. And I never feel quite so disabled as when I try to get upstairs first thing in the morning. Our bedroom is in the basement so I start each day keenly aware of my limitations before I’ve even had my breakfast. I mean, rude.

We’ve been working with an architect and a contractor to plan our remodel and let me just say that I am almost giddy with relief that we hadn’t gotten around to doing this before my diagnosis. Ideas for the house have been informed by necessity; it turns out that disability has matured my concept of home. I look at our plans not through the lens of how I will live in my house, but how I will die in it.

I’ve always sort of thought that way, of course. You can’t grow up around dying people without being aware of how your house fits their needs, or fails them. For years I pushed those thoughts away as morbid or unneeded, mostly because going down that road led to emotions I wasn’t really prepared to handle. Now that my needs are the ones that need to be addressed, it’s actually easier to talk about.

Like, I had to say out loud that I did not want to be in a hospital bed in our living room, the way my dad was for three years before he died. I want a bedroom big enough for family to come visit, but with a door that closes so I can do my sick person things in peace. I want my bathroom to have a toilet with a bidet or hand-held sprayer so I can clean myself by myself for as long as I am capable. I want to look through large windows and see the sky.

I want my kitchen to have various heights of kitchen counter so I can putter around no matter how little mobility I have left. I want to knead dough in a wheelchair, and check on the turkey without having practically crawl on the floor.

I want a motherfucking ramp.

And I want a chair lift so my sister and I can do wheelchair karaoke in my basement forever.

Universal design was just a concept to me a few years ago. Until my diagnosis, I was still looking at our house remodel through a very narrow, and very ableist, lens. Pictures I clipped for inspiration were nothing more than aesthetic. I thought of shaker cabinets, schoolhouse lighting, hexagonal tiles. But there was nothing real behind that. No thought past what would tickle my Better Homes and Gardens fantasies.

Being forced to grapple with how I will move through a space as my mobility declines – whether from Schwannomatosis or blessed old age – is making the entire design process focused in ways I never knew could be. . . healing. Like, I have a genetic condition so there is a 50/50 chance I have passed this down to my children. Instead of sitting in a vortex of worry over what ifs, I can look at specific solutions. Instead of feeling like I’m dooming them to life with a disabled parent, I can show them how functional disability can be. Can I tell you that, as the daughter of a quadriplegic, the idea of functional disability is a gift.

A lot of people have asked over the years why we’re not moving, instead of going through the enormous expense and hassle of remodeling our house. Shoreline still has a lot of ramblers, was the suggestion. As if we hadn’t already talked about and discarded that option a hundred thousand times.

For a long time I felt embarrassed by that question, as if I was doing something ridiculous or wrong by pouring so much into a house. But the farther we get into this process, the more I understand why it makes sense. Having looked at the Seattle housing market, at the almost criminal dearth of accessible homes available, my family would have to remodel anything we could afford anyway.

Also, it all comes back to the beginning: the first time we walked into the house and knew we wanted to buy it. We didn’t care about the house. I mean, we love our house and I always say that we bought it on purpose. But we care about the place. We bought property in the neighborhood we wanted to live in, and have spent the past ten years putting down really solid roots despite my desire every day to pack it all up and move back home.

I am home here, in this space. On this street, with these neighbors, and the friends I hope my children will have for life. My doctors are close enough that driving to appointments isn’t too uncomfortable, and I can get around by bus on days I can’t drive at all. I can do most of my errands on foot, or in my wheelchair whenever that day comes. I live here. Like, really live. And I can see myself living here for a really long time.

Now all I have to do is put my weight behind transforming this rough, drafty, chopped-up box into a home I can die in as comfortably as I can live. That can help me put off that dying part for as long as possible because I won’t have to fight against my own house in order to survive. It’s a big project, and we’re just at the beginning of it. But for the first time since my father was paralyzed, I feel like maybe it’s okay to inherit his condition. Maybe it’s okay to die at home after spending years dying at home. Like, maybe that’s the way it’s supposed to be.

I mean, I’m going to die at some point anyway. May as well figure out how to live in the meantime. It just so happens that I live with a disability, so I guess that’s what I’m going to do.

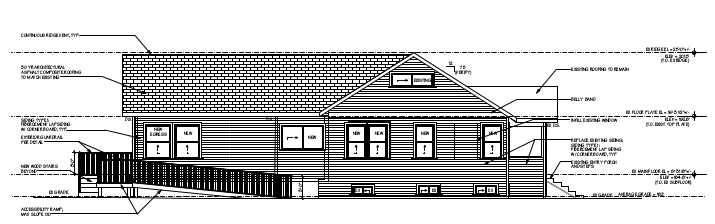

image: initial design of what I hope will be our remodeled house

Wheelchair karaoke 4EVA!

YESSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSS